A few weeks ago, I was browsing Pinterest and stumbled upon several articles titled “Do you need character arcs in your story?” I was surprised and immediately thought: that’s like wondering if you need story to tell a story.

There is no question about it: YOU NEED CHARACTER ARCS. If you don’t have character arcs, you don’t have a story. Because your characters’ transformation is the story, not the “stuff that happens.” That’s the plot, and yes plot is important — but not half as important as the character arcs.

So it’s not a question of do you need characters arcs; it’s a question of how do you write powerful character arcs?

You know what drives me crazy? Books that either a) don’t have character arcs, or even worse: b) have character arcs that leave the character a worse role model than they started the book as. Some people might call this a “negative character arc”… but they would be incorrect.

Here’s the thing about negative character arcs: they are meant to be understood as negative. It’s obvious to the reader that they are not reading about a role model character. In fact, the main character has turned from protagonist to antagonist (or at least something very similar) and no reader in their right mind would want to emulate that character.

On top of that, I just don’t see the point in writing a negative character arc for your protagonist. Don’t throw tomatoes at me, but I believe writing is a very sacred and important job. Words are world-changing. The more positive stories you put out into the world, the more positivity you inspire. I don’t know about you, but I want to create more good in the world — using the powerful tool that is writing.

You with me? AWESOME.

All that to say: today we’re going to go over the essentials of crafting a powerful character arc that not only inspires your readers, but leaves them thinking long after they close your book.

Before you begin, ask yourself why.

Before you even begin to structure/outline your character arc, you have to get quiet and ask yourself why.

“Why do I want to write this story?”

Really think about why the story is important to you — whether it conveys a message or theme that is relevant to your life, or a truth that only recently dawned on you. The point of writing a character arc is to weave truth into your story, but in an artful way (not a preachy way.) Your character is going to have an “aha moment”, which will inspire thought (and maybe even an aha moment) in your reader.

That’s how you make a reader think. Not by yelling your message at them, but by deftly weaving it into your character’s story. A well-told story is the crowbar which opens the reader’s soul and lets them see the truth you see.

So take a few minutes to think about and write down your reason for writing this story. What does the theme mean to you personally?

Remember what an important job it is to be a storyteller. You give the world far more than just an entertaining story — you give them insight and truth, if you choose to. And even if you don’t try, your story is carrying a lesson to your readers, through your characters.

Map your powerful character arc

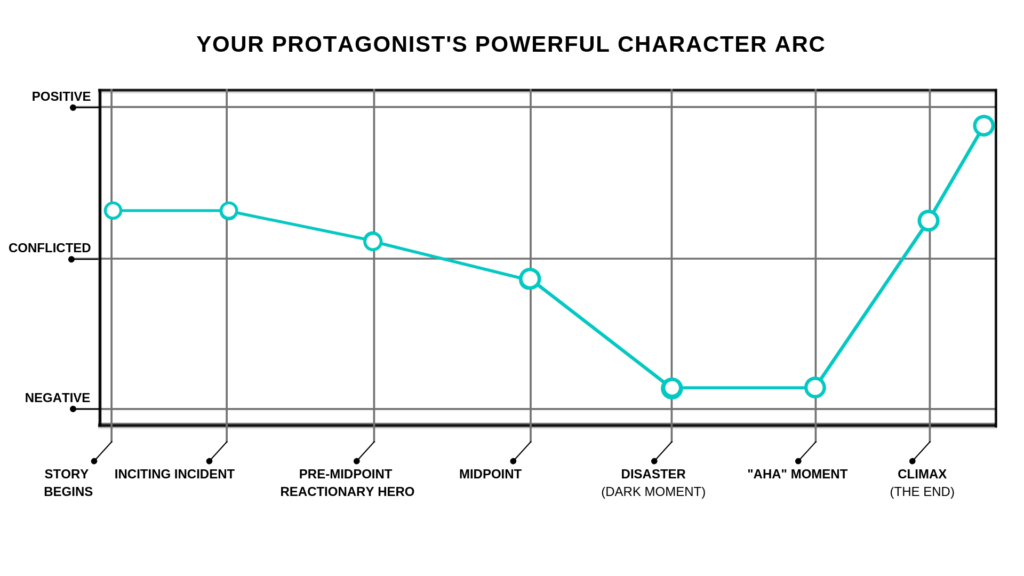

Okay, now that you’ve figured out your “why”, it’s time to move onto actually mapping your powerful character arc. We’re going to go through it in sections, according to different “beats” in your story. (You might notice some similarities to the 3-act story structure and that’s because I love and use the 3-act story structure all the time. And this character arc template pairs beautifully with it.)

Here’s the character arc we’ll be following today (pictured below.) I want to show it to you first, then “zoom in” to each story beat and reveal it more in-depth. (Also, at the end of this post, I’m going to give you a free template including a CUSTOMIZABLE VERSION of this map!)

THE OPENING

Of course, we have to begin at the beginning. With all this talk of positive character arcs, you might think I’m going to suggest making your protagonist a role model throughout the entire story — an angel from beginning to end.

NO WAY. Not only would that be ridiculously unrealistic (and unrelatable) but it would defeat the whole purpose of your theme. A character who is already enlightened can’t have an “aha” moment — and can’t deliver a powerful message to your reader.

That’s what a character arc is for.

So when your story opens, your protagonist is a disaster waiting to happen — or already happening. That’s why I placed their starting point (in the line chart) just north of the “conflicted” state. They’re probably a good person at heart, but they have some serious issues and false beliefs. (AKA: they’re primed to NOT make the right decision when something goes sideways… and something is definitely about to go sideways.)

Why is your protagonist a disaster waiting to happen? Because they have a deeply-rooted fear and misbelief that has been hidden in their psyche for a LONG TIME — and it’s only going to take a spark (an inciting incident) to make them act upon their fear and misbelief, and turn their life upside-down.

When a story first opens, nothing hooks the reader except for one thing: your protagonist’s inner conflict. In a nutshell, that means: desire VS fear. How is the protagonist’s fear standing in the way of getting what she thinks will make her truly happy?

That’s the question you have to answer before you can write a powerful opening to your novel — an opening that hooks readers and pulls them in for the whole ride.

So many writers miss out on this because they’re so busy building the character’s world. If I could advise against one thing, it would be DON’T BUILD THE CHARACTER’S WORLD. Nobody really cares about a world or setting (a world doesn’t have feelings, a setting doesn’t have emotions.) We care about what’s going on inside the protagonist. That’s what readers are going to connect with immediately… and then, once they’re engaged, they’ll be ready to explore the world. Save it.

Read more about writing a strong opening in this post: How to Write a Strong Opening for Your Novel (The Secret to Hooking Readers That Nobody Talks About)

WANT SOME EXAMPLES? HERE ARE A FEW POPULAR STORIES THAT NAIL THEIR OPENINGS:

- A Christmas Carol: our main character, Scrooge, is a mean old miser who loves money and hates Christmas — but his internal conflict runs much deeper than that. We can see that he must have been a good person once, but over the years has become a jaded mess. We see him turning his back on the world — but most of all, on the good in the world.

- Pride And Prejudice: our main character, Elizabeth Bennet, is one of five girls facing financial ruin if they don’t “marry well” before their father dies. The stakes are set, but Lizzy throws a monkey wrench into the whole situation: only the deepest love will persuade her into matrimony.

- The Greatest Showman: our main character, P.T. Barnum, is a poor boy with a million dreams. As he grows up and struggles to make ends meet, he constantly battles his insecurity of not being/having enough, and his ambition to make his dreams come true, against all odds.

THE INCITING INCIDENT

We all know that the inciting incident is what really gets the ball rolling in a story. But it doesn’t have to be some big, epic, crazy call-to-adventure. It just has to be something that pushes your protagonist outside her comfort zone.

I have a rule about “the first 5 minutes” of your story. Essentially, you want to take normal pacing and chop it in half. Most story structures will tell you to make the inciting incident happen at around the 12% mark of your story. But I try to shoot for something more like the 6% mark. I mean, come on. We live in the age of instant gratification and short attention spans. If something juicy is going to happen in your story, cut to the chase. Don’t lose your readers before you even start.

But where you place the inciting incident isn’t half as important as why your inciting incident matters. Think about this for a while, and write down your ideas: why does this inciting incident matter to your protagonist? How does it push her outside her comfort zone? How is she going to respond to it, based on the fear that has raised her?

Your protagonist’s fear has been quietly growing stronger for a long time now, which means when something happens to push her outside her comfort zone, she is going to react to it with something familiar, fighting to stay inside her comfort zone. Her fear takes over and she responds to the Inciting Incident all wrong, setting up more obstacles for the rest of the book.

It’s really as simple as that. Don’t overcomplicate it, as many writers do. If you know why the inciting incident matters to the protagonist and you let her react to it as a normal person would (running for cover bc of her fear!) CONGRATULATIONS. You nailed it. Let’s move on.

BUT FIRST! A FEW STORY EXAMPLES TO HELP YOU PICTURE THIS:

- In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge is visited by the ghost of Jacob Marley, his late business partner, who warns him to change his selfish ways and tells him about the three ghosts of Christmas that will come to visit him. Shaken (but still his cynical old self,) Scrooge reacts to this inciting incident by waiting up for the prophesied ghost — just to prove the whole thing wrong.

- In Pride And Prejudice, the Bennets go to the Meryton ball and meet Mr. Bingley and his friend, Mr. Darcy, who proves himself to be proud and uncivil. Hurt by something she overhears Darcy say about her, Lizzy makes up her mind to loathe him for eternity.

- In The Greatest Showman, P.T. Barnum loses his day job and worries about being able to support his family. But instead of seeing it as a setback, he sees it as an opportunity — to finally make his dreams come true. He decides to start the circus venture.

THE MIDDLE

Depending on your plot, this “middle” section will look different for everyone. But if you’re using the 3-act story structure it will play out something like this:

REACTION, PLOT TWIST, ACTION

The decision your protagonist made after the inciting incident is something she’s still paying for… She made a fear-based decision (backed up by her misbelief about the world) which means she’s not responding — she’s simply reacting. The same goes for any obstacles that appear in her path, however large or small.

Now, when you reach the midpoint of your story, it’s time for the plot twist, or as I prefer to call it: the game-changing midpoint. This doesn’t have to be some crazy twist of fate that nobody saw coming. If it is, awesome! But if you’re writing contemporary fiction it might be hard to get super dramatic with your midpoint.

Don’t panic. The only thing a game-changing midpoint has to do is shift the protagonist’s goal and surprise the reader (it doesn’t have to be a big surprise, either!)

Remember: the game-changing midpoint usually leads to some bad decisions on the protagonist’s part, as she THINKS she’s doing the right thing, but is actually doing just the opposite (still trying to avoid the thing she’s afraid of.)

This isn’t the “aha” moment, yet. Protagonist is still in survival mode, but now she has a plan and is actively pursuing it, thinking this path will actually bring her to where she wants to be. Little does she know, disaster is on the way.

SOME GREAT EXAMPLES OF THE MIDDLE CONFLICT, FROM POPULAR STORIES:

- In A Christmas Carol, after going on a journey with the ghost of Christmas past and Christmas present, Scrooge begins to see that there are some things money can’t buy. He wrestles between the truth and his misbelief, as he omnisciently witnesses the events of the present — the impact he is currently having on his world.

- In Pride And Prejudice, the complicated relationship between Lizzy and Darcy reaches a boiling point when Darcy proposes. But even while asking Lizzy to marry him, Darcy manages to offend her. Lizzy spurns him for his prejudice toward her family and leaves the situation in more of a mess than how it started.

- In The Greatest Showman, as Barnum continues to chase his idea of success, he loses sight of what truly matters. His character arc takes a dive at the midpoint of the story, when he turns his back on the circus performers, proving to them (and the audience) that he’s changed for the worse. But he doesn’t see anything wrong with what he’s doing, and thus continues down the path of destruction.

THE DARK MOMENT

DUN-DUN-DUNNNN… Disaster strikes! Remember, it’s going to take a major low moment for your protagonist to come to her senses. She has to be utterly and completely broken, confused, lost, and disappointed. In other words: this is the fun part.

How you decide to break your character is totally up to you. But don’t get so caught up in the disaster itself that you forget the reason why it matters to the protagonist. Obviously, some disasters would be disastrous for anyone. But that’s where a lot of writers go wrong: they start thinking “this would be horrible for ANYONE to deal with!” But you have to go deeper than that.

What does this disaster personally mean to the protagonist? How does it force them to realize that they’re the one to blame for this crisis? How does it completely disarm them and make them face off with their fear and misbelief?

It’s always darkest before the dawn. Your protagonist needs a rock-bottom moment in order to have an “aha” moment — and that’s what makes the revelation so sweet and satisfying.

CHECK OUT THESE GREAT “DARK MOMENTS” FROM OUR EXAMPLE STORIES:

- In A Christmas Carol, Scrooge’s dark moment arrives with the Ghost of Christmas Future. He gets the opportunity to look into a “crystal ball” and is shocked by what he sees: Tiny Tim’s tragic death, and even more chilling — Scrooge’s own funeral, which seems to be more of a celebration than a loss.

- In Pride And Prejudice, Lizzy’s younger sister Lydia scandalously elopes with the dastardly Mr. Wickham, destroying her sisters’ chances of marrying well. Lizzy feels somewhat responsible for not warning her sisters of Wickham’s deceit, and now it seems too late to make anything right.

- In The Greatest Showman, Barnum’s whole life comes crashing down when his circus building burns to the ground. At the same time, a scandal comes out in the news that threatens to tear his marriage apart and destroy his last shard of happiness.

THE AHA MOMENT

This is where your character arc gets good. After your protagonist has been brought to their knees by the disaster, they have a revelation — an aha moment. They can suddenly see how their fear and misbelief has led them to make the wrong decisions about everything. They realize how wrong they were — but most importantly, they see that they’ll have to overcome their fear and make the RIGHT decision in order to achieve their goal: true happiness.

So how is your protagonist going to overcome their fear and continue to the climax, therefore developing as a character? What lesson are they going to learn (and simultaneously teach the audience?)

Only after your protagonist has their “aha” moment can they continue to the climax. Without this revelation, they don’t have the courage to face their biggest challenge yet. But with this revelation, the protagonist can finally overcome her fear, crush her misbelief, and show the reader how much she has grown and developed since the beginning of the book.

SOME GREAT “AHA” MOMENTS FROM THESE POPULAR STORIES:

- A Christmas Carol: After his whirlwind tour of the past, present, and future, Scrooge is transformed. He has an “aha” moment when he realizes that he still has time — he can change, and maybe even change the future for the better.

- Pride And Prejudice: Lizzy has an “aha” moment when she discovers that Mr. Darcy not only helped patch up the Lydia/Wickham scandal by getting them to marry, but also aided in reuniting Bingley and Jane. She suddenly realizes how wrong she was about Mr. Darcy — and how prejudice she was, herself.

- The Greatest Showman: At his lowest moment, Barnum’s circus performers show up and help him back on his feet. They help him to realize that by “chasing the cheers” of people who didn’t matter, he lost sight of the whole reason why he wanted to be successful in the first place: for his family. Barnum’s “aha” moment — and the truth his character arc teaches the audience — is that true happiness is found not in receiving praise from others; but in relationships with the people you love.

THE ENDING

By this point, we’re well into the final act of your story. But one last thing has to happen: THE CLIMAX. This is the moment everyone has been waiting for, where the protagonist is going to face their most difficult challenge yet. It’s a true test of their character — and how they respond to the situation is the proof that they’ve changed.

So your protagonist has already won the internal battle (in their “aha” moment) but now it’s time for them to win the external battle (which of course will force them to face off with their greatest fears.) Once that’s over and done…

THEY ALL LIVE HAPPILY EVER AFTER. But, actually, they don’t have to. The ending doesn’t necessarily have to be happy; but the protagonist does have to come to a realization that their misbelief has been just that — dead wrong. The protagonist does have to change as a result of her journey. That’s what makes a character arc powerful.

If your reader doesn’t know how the character has transformed as a result of her journey, you need to rewrite your book until they do.

At the end of the story, your reader should feel contented with the message of the book because the character HAS changed for the better, even if she wasn’t able to make things right in the end. Sometimes it’s just too late to make things right — but that can be a poignant theme in and of itself. One that will evoke thought and maybe even change the lives of your readers.

WANT TO SEE THE PERFECT ENDING IN ACTION? LET’S LOOK AT OUR STORY EXAMPLES ONE LAST TIME:

- At the end of A Christmas Carol, Scrooge mends his ways — and proves his transformation — by giving to the poor, healing his relationship with his nephew, giving generously to the Crachits, and “keeping Christmas well” for the rest of his life.

- At the end of Pride And Prejudice, Darcy proposes to Lizzy again — and this time she accepts. They both repent for their misconduct toward one another, and come to the realization that they have always been more alike than they ever were different.

- At the end of The Greatest Showman, Barnum makes amends to his wife and invents a way resurrect the circus. But, after learning what truly matters in life, Barnum decides to pass the baton to his business partner and spend more time with the people he loves most — knowing now that family is “everything you ever need.”

Take your story to the next level

That was a lot, I know! Believe it or not, I could talk about all of this so much more. But I don’t want to get too complicated. The formula for a powerful character arc is actually really simple — and that’s why I created this template for you.

It’s a cute little printable that goes over everything we just talked about in this post — but in a fill-in-the-blank style, so that you can customize it with your own unique story beats and craft a truly FLIPPIN’ AWESOME character arc. PLUS I included the line chart pictured at the top of this post (only it’s special bc you can customize it with your own story beats!)

TALK, BRO

Phew! What a post! Do I ever shut up about storytelling? NOPE. Tell me in the comments: how do you feel about character arcs? Do you see room for improvement with your own? What are some of your favorite character arcs in fiction or film?

LOVE THIS POST? PIN IT!